An eternity ago, my senior year of high school, I was cast as Judy in our production of Rebel Without a Cause. The role was a challenge, a great chance to learn more about myself as an actor. The role also demanded that I kiss Jim Stark. Whenever we rehearsed that scene, “Jim” and I would recite our lines and simply look at each other, then go back to lines. In our last run-throughs, “Jim” and I rehearsed as we always had–but this time, our director called out, “We need the kiss!” Every single head in the room whipped around to look at us. “Jim” and I both turned bright red, embarrassed and terrified. We did the lines, kissed, finished the scene, and walked offstage.

That experience taught me a few things about directing intimacy. First, everyone needs to be comfortable, and everyone finds comfort at their own pace. Second, communication is really important to creating that comfort. Intimacy isn’t just kissing onstage–it is any close physical contact, from the romantic to the violent. Decades later, I’ve directed a wide range of shows that require intimate moments, from Romeo and Juliet to The Philadelphia Story to Spring Awakening. Each show is wildly different, but the principles of intimacy direction remain the same. And as the director, I set the tone for how we will handle intimacy.

Take time to do table work.

On a tight rehearsal schedule, it can be very difficult to set aside the necessary hours to work through the scene. But discussing the lines, tactics, and motivations can open up opportunities for the actors to express their own feelings about the scene. Having a safe space of conversation builds rapport and trust–and as the director, it’s vital that your actors trust you and know that their feelings matter to you.

Discuss consent.

Any time actors are going to be touching or close together, everyone needs to understand how important it is that touching only happens with permission. Being in rehearsal isn’t automatic consent. Have a consistent warmup or activity that everyone participates in which establishes a community. Many intimacy choreographers advocate for a tap in/tap out method. Tapping in–even just a high five with a scene partner–is a nonverbal way to say “I am ready.” Tapping out (another high five) reminds everyone to leave rehearsal behind. These boundaries for consent are important, both physically and emotionally.

Know your actors.

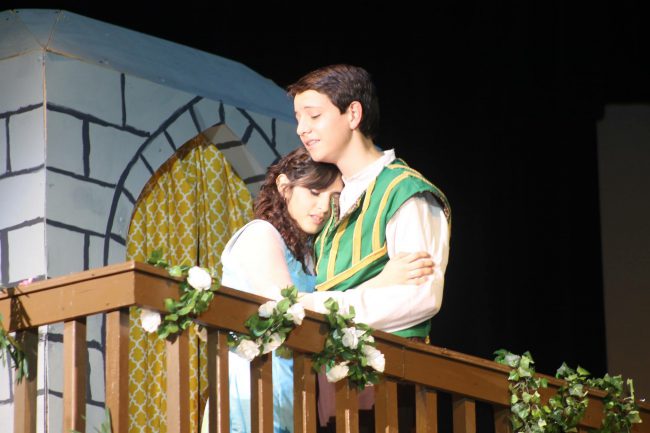

When I directed Romeo and Juliet, the leads were very talented and very shy. It took time for them to feel comfortable, so I began with simple exercises to help them. At the top of every rehearsal, I covered the agenda and objectives with the cast. I requested that Romeo and Juliet sit next to each other during that meeting. Then, a few rehearsals later, I asked that they hold hands. By the third week, whenever they weren’t onstage, they needed to be touching in some way (hugging, holding hands, arms around each other). Eventually, they were able to do those famous Romeo and Juliet kisses without blushing and laughing.

These intimate moments can happen during scenes of violent activity as well. When rehearsing Les Misérables, as the students fell at the barricade, I had to work very carefully with each of them to know how they felt about the activity–it wasn’t enough to say: “Just do it because I said so.” When Gavroche was shot, the actor was at the top of the barricade, and fell into the arms of two other actors that she trusted completely. During the firefight, another actor was going to stumble off the barricade and be caught–but she was very protective of her body and how she was touched. I allowed her to pick the person who caught her, he was comfortable as well, and the scene was a success.

Limit the spectators in an intimate rehearsal.

When it came time for Romeo and Juliet to actually kiss in rehearsal, they were the only ones there. In fact, the first time they “kissed,” they only touched noses. More than that, because they were very shy, I told them to run the lines, kiss when they were ready, and I’d be nearby doing something else–not even watching them. In fact, whenever I block the scenes that have kissing, I offer the actors the opportunity to rehearse the moment away from everyone else (even me).

Spring Awakening has heavy intimacy. In our rehearsal for the end of Act One, I only had Melchior, Wendla, and my stage manager. I walked Melchior and Wendla through the specific movements they needed to do, and when in the script (and music) those movements needed to happen. We talked through it, and then my stage manager and I went to another area of the rehearsal space to talk about the show–Melchior and Wendla had the space to discuss and practice the scene without anyone staring at them, but they also knew we were close by if they had questions.

When there is stage combat, it is just as important to limit the rehearsal, especially with younger actors. While blocking and choreography the big Tybalt-Mercutio-Romeo fight, I had only those three actors and Benvolio. I didn’t want any distractions, any spectator noise, anything that could compromise safety. Each actor had to focus very carefully on what they were doing in the moment so that they could be confident with each (controlled) swing of the sword.

Choreograph the moments for consistency.

Being consistent ensures comfort and safety. Swinging rapiers are always dangerous, but having consistent timing, angles, and steps will lessen the danger. When actors are feeling confident (especially the teenagers), they might try to add new flourishes or effects–which is a huge no! There is no sudden improvisation in stage combat or intimacy; actors can make suggestions–such as “what if I …”–but they cannot just “try” something because they wanted to. That lack of communication can damage trust and ruin the safety and comfort of the rehearsal space.

Directing intimacy is challenging and potentially uncomfortable. Success in directing intimate moments comes from experience and reflection–the anecdotes above are times I got it right. There are also plenty of times I had to reevaluate my approach because I wasn’t communicating clearly or my actors were struggling with the requirements of the role. The most important thing I can do as a director is ensure that my actors have a safe space to work and let them know that their safety matters to me. We develop trust, and ultimately, we come away with a great show.