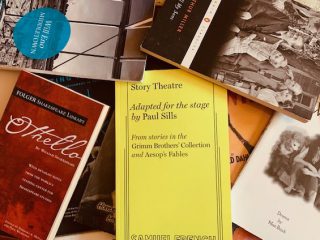

Long ago, I went through an acting program that was transformational for me when it came to my performance abilities. I learned a variety of techniques to help me connect to characters, respond organically in the moment, analyze a script. I had meaningful acting experiences and rigorous classes spanning many specific subject areas. I learned the theories of several different directors and practitioners, and left with various tools to tap into my roles. Blah blah blah, the point is: I am much more skilled than when I entered that program, and I attribute so much of my performance ability to what I learned there.

That being said, when I left that acting program, I didn’t act for 8 years. Not because I didn’t love it and not because I didn’t feel good at it, but because I was sure that this was not a healthy path for me to continue down. In my last blog, I talked a lot about how my body was treated and spoken about, which was certainly part of my fast exit. But it was more than that, too.

The program was rigorous, the expectations were high, the feedback was sometimes too personal and not often kind. I was witness to enough experiences that felt unconstructive, overly critical, or unclear in their purpose–even in retrospect. It is worth noting that performing can be a brutal business, and a thick skin is certainly a helpful attribute for a theatre practitioner to have. Professors worked hard to prepare us for the realities of the industry, which unfortunately led many of us to, well, leave it. I’m sure as our teachers, some were just trying to make sure we were ready.

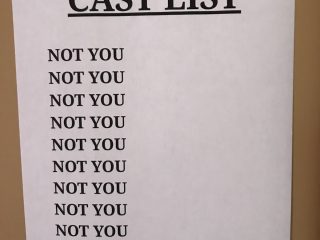

Maybe you could say we weren’t cut out for it; that’s certainly how I felt. But are we to assume that theatre programs are only made up of people with stereotypically industry-standard bodies? Full of people with supreme confidence and unwavering mental health? Who are consistently unflappable in the face of rejection, and who’ve never had a pause in their insatiable work ethic and drive? What about brilliant performers who don’t yet see themselves represented in actors across the screen? Who spent their childhoods searching for characters who looked like them? Should they be driven out so that the industry can continue to perpetuate their exclusion?!

Whew. Sorry, getting heated over here, y’all.

As a theatre educator, I have to wonder if a little more empathy, a little more leeway and a little more patience would have led us to feel prepared and empowered, rather than scared off.

You can acknowledge that the road is bumpy without implying that few are worthy enough to travel it.

A rigorous program that turned out so many skilled performers and technicians. But what good was our skill if we abandoned it?

Meanwhile, I’ve also seen some workshops and programs that are so much about validation that they’ve left no room for technique or high performance expectations. What do we learn about growth and consequences if we live in a Sea of Yes?

So what does healthy rigor look like? Well, I’d argue that building a safer space facilitates healthy rigor.

Some think that “safe space” means that there is no room for constructive criticism, critical thought or high expectations. But I believe that safety should allow us to take risks, rather than shield us from them.

The less safe your environment, the more likely that your intense and rigorous program is causing harm as it builds skill.

Creating a safer space means intentionally establishing trust and building relationships from the very start. Forming a sense of community is important in any group with high expectations. Feeling that we are individually known and valued, as well as a functional part of a larger group, yields a safer space through which we can be challenged to risk more, learn more and produce more.

There’s a difference in working hard because you’re invested in a group and program…and working hard out of competitiveness, fear, or desperation to prove your worthiness.

What might this look like in practice?

My friend and colleague Alicia Greenwood is a lovely high school educator who does an awesome job creating safety to promote rigor. Alicia has always allowed students to eat lunch in her classroom, finding opportunities for them to connect outside of class and rehearsal. She has a great mentorship program where the older students are there to welcome new participants and ensure everyone feels connected. She offers low-stakes summer theatre opportunities where students have a lot of time for friendship and play. During the school year, she begins her rehearsals by checking in and catching up before starting the work. When the actual rehearsal begins, it is highly collaborative and student-centered. Students work in various groups, brainstorm together, pitch ideas and creations, and give thoughtful feedback.

Alicia begins her play processes in what she calls “The Period of Yes!” This is where students present ideas and everything is on the table. She lets her performers and technicians explore a variety of different concepts, even if they aren’t in line with her initial directorial vision. Even if she doesn’t see their immediate relevance to the project right away, she allows them to be explored and is open to being convinced. She takes this time to validate their thoughts, encourage creation, make opportunities for collaboration, and to hear every voice. Her high-schoolers feel like worthy and heard members of the community, and they trust that their director values their contributions.

Then begins the “Period of No.” As production nears, ideas have to be whittled down based on her vision and concepts, budget and time period. At that point, ideas are taken off of the table. New presentations of ideas or solutions are always listened to and considered, but she doesn’t pretend to entertain something that will not work for her. The focus switches to precision, to execution. Copious notes are given.

But the notes are being given from a person who has shown kindness and instilled a sense of value. She is trusted. She has proven that she will receive ideas and brainstorm alongside them, and they then accept when an idea is not suited to the direction in which they’re all going–together.

That’s what safety looks like in one program, in one school. But I’m confident that there are tools and strategies that are authentic to any program leader that can be used to build a safer space for rigor that is both healthy and productive.

The goal is empowerment, growth, confidence—AND some dang good theatre. And generally, I just prefer it when people are kind.

The road may be bumpy, but we’re all worthy of traveling.