When people ask me what my dream acting job is, or where I would love to be professionally in five years, or any of the usual “what’s your acting fantasy?” questions, my answer is always the same: the dream is rep. Yes, a true repertory contract is the dream. A repertory theater can be defined as an ensemble of performers hired for an extended period of time in which they will appear in multiple, often-overlapping shows, and play a variety of roles. In her wonderful memoir, I Will Be Cleopatra, the late, great actress Zoe Caldwell describes her early experiences with the repertory theater system thus:

There are many different forms of repertory. Weekly repertory, fortnightly repertory, and the big regional theaters where as many as three or four plays are rehearsed and fed into the season … you have to be fit … All young actors should be so lucky. Every two weeks a new part, a different play … Never did any company member ask to play a particular role and there were no leading players. You played what you were given no matter how large, no matter how small. You were a company member and served the company. That was your job … We performed every playwright, including Shakespeare, Shaw, Sheridan, Miller, Coward, Williams … It could have made a marvelous country actually, everybody being used and important but not too important. It was, in fact, my country, my world.

Zoe Caldwell. I Will Be Cleopatra. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001, pp.52-3.

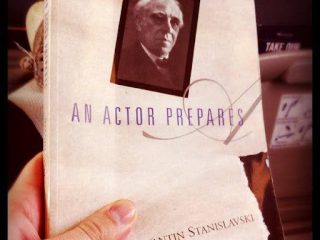

Ah! What a beautiful evocation of an acting utopia, a demi-paradise of performance! Who wouldn’t want to grow, stretch, and develop in such an environment? Caldwell attributes her foundational theatrical learning to the rep system: a safe place where she was constantly put to work in different and challenging ways.

And yet this same acting repertory theater system that so fed Zoe Caldwell and countless other performers is —for all intents and purposes— dead in present day America. Why? Why has this once ever-present and ever-popular theatrical structure all but vanished? Where has repertory theater gone?

In many ways, the history of theater is the history of rep. In nearly every age, troupes of actors have been learning multiple roles in multiple plays simultaneously and performing them on alternating nights, whether in a single theater or on the road in multiple locations. Ensembles of actors having been “touring the provinces” since time immemorial. How better for young actors to learn from old? For performers to hone their craft or expand their range? And (crucially) how better to maximize profits for the owners of the acting companies? Rather than presenting their audiences with a single dramatic offering, it was much more financially adventurous to present a variety of theatrical dishes, a performance pu pu platter, if you will. The same group of actors could enact comedies or tragedies, all manner of stories, thus multiplying the opportunity for income. Audience members were inclined to return again and again, to follow their favorite performers through their various guises (in much the same way we follow athletes today). Rep survived through the centuries because it made financial sense.

So what happened? Where did it go? In twentieth-century America there were still a substantial amount of repertory theaters. The great mid-century regional theater movement saw a great migration of theatrical talent away from hubs like New York and into new markets, where a multitude of new theaters were established in various states. Many of these venues were rep companies, presenting a season of work performed by a single group of performers. However most of those companies that still exist today have abandoned the rep model.

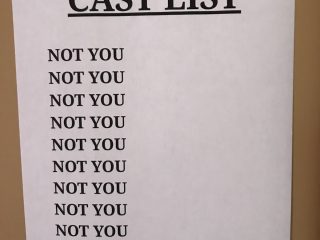

Part of the reason is (again) money. That’s right: the same thirst for profits that sustained the rep system might have also spelled its undoing. As theatrical interest waned and ticket buyers dwindled, it became more cost-effective to hire actors on a per show basis, rather than keeping a large ensemble on the payroll all year. Plus, as film and television became a huge industry, acting talent started moving away from the smaller theatrical towns and towards the bright lights of Hollywood. Actors were suddenly less likely to commit to a long rep contract when other, more lucrative cinematic work might come calling.

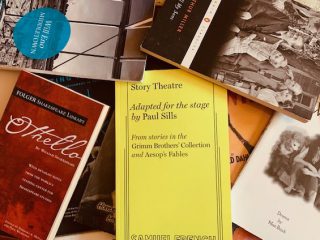

Another part of the reason rep is no longer the dominant theatrical structure in the USA is the much-needed (and much-belated) diversification of theatrical lineups. Few present day theater companies perform just one kind of play–even most Shakespeare festivals do more than just Shakespeare these days. The vast majority of American theaters program a wide variety of plays in a wide variety of styles that require a wide variety of actors. A single repertory ensemble would not, and should not, be able to cover all the given roles in a season. On a purely technical level, musicals require different skills from Shakespeare, which, in turn, requires different skills from an avant-garde, experimental new work. Even the most well-rounded actor can’t do everything! The “one-size-fits-all” rep style of fitting plays to the dimensions of your given group of hired actors is no longer appropriate. Rather, the casting must reflect the unique needs of each individual play.

Besides the stylistic diversity of the shows being programmed, there’s also the fact that contemporary plays are about a whole bunch of different kinds of people. Each new play requires a different collective of performers. This move away from white, straight, western-centric plays is part of a larger shift in theater, and art in general, towards expressing the full spectrum of the human experience. This shift is vital if theater as an industry is to have any relevance going forward. Perhaps rep companies hampered this expansion by forcing theater runners to tailor their seasons to one set of actors. Hiring performers for a single given show (ideally) allows companies to put all kinds of people on their stages: artists of every type and sensibility, bodies of every shape and color, storytellers of every culture and lived-experience.

There are still a handful of companies in the United States that follow the rep model: the Oregon Shakespeare Festival comes to mind. Other companies, such as The Guthrie in Minneapolis or the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco, were founded as repertory companies and slowly evolved away from the model over time. Yet, rather than mourn the death of rep, let’s look at the beautiful ways in which theaters have been evolving in recent decades to reflect the world around them more accurately; the beautiful ways in which theaters have been embracing their communities through outreach and education; and the beautiful ways in which theaters have been widening the net, expanding the traditional notions of what and who belongs on a stage. Perhaps one day rep as a hiring system will return in some new form. Perhaps theaters will find ways of keeping more actors employed for seasonal contracts. And perhaps the amazing learning opportunities true repertory allows (those vital, dynamic, and formative years so crucial to Zoe Caldwell’s development as an actor and a person) will return in some new guise. The future of American theater is unknown, but bright with possibilities.