As we lean into the warmer months, you may be starting to dream of summer Shakespeare outside. Perhaps you’re in a field, or perhaps in a lovely old amphitheatre. Perhaps there are birds chirping, or perhaps you are under the stars. The poetic words of centuries ago are mingling with the organic sounds of the natural world. There is nothing quite like the bliss of enjoying good classical theatre under an open sky. But how did this practice, an annual cherished tradition in many, many communities, come to be? Today we are going to explore outdoor Shakespeare: its history and traditions, its joys and difficulties, and its many forms and characteristics.

It all started with a Globe. Or more specifically: The Globe. The original Globe Theatre in London was built in 1599 by Shakespeare’s acting troupe, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. Shakespeare, a shareholder in the building, wrote many of his plays specifically for that “wooden O”. The particular shape of the building (a raised platform jetting out into a roughly circular yard, with viewing boxes encircling it all) was reminiscent of the town squares and inn yards where traveling players would set up and perform on the road. Many of Shakespeare’s most iconic stories were conceived and originally staged in that beautiful outdoor amphitheater. Imagine close to 2000 people crammed in, talking, arguing, eating, laughing. It was from that sweaty, messy, raucous, and vital atmosphere that these plays first emerged, as robust as the theater that housed them.

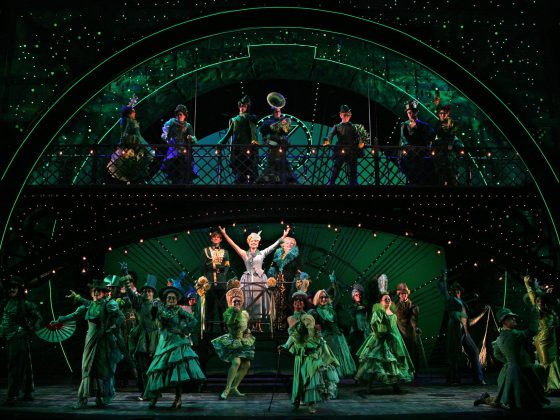

Then for a few centuries, Shakespeare largely moved indoors. During the Restoration, Shakespeare’s plays started being presented on indoor proscenium stages, with increasingly elaborate sets and special effects. Liberal changes were made to the text as the plays were molded to match the more lush, epic theatrical style now in vogue. The plays were trimmed, truncated, and tamed, the performance style less wild and more rarified. It is here that the lofty, high-minded reputation of Shakespearean Performance began (a conception that, whether accurate or not, persists to this day).

It wasn’t until the 20th century that a concerted effort was made to return performance practices to a facsimile of Shakespeare’s original conditions: rough platform, direct and clear style, natural sky above. The Shakespeare Festival movement in the United States was kicked off by Angus Bowmer in Oregon. He founded a Shakespeare Festival in the small town of Ashland, Oregon in 1935; the Oregon Shakespeare Festival is the grandaddy of them all and soon many, many more such festivals followed.

Some of them attempted to replicate the Globe, or a physical, theatrical space similar to those of Shakespeare’s day. Other festivals sprung up in fields, in barns, at universities, on beaches, and alongside lakes. The Delacorte Theatre was constructed in the middle of New York City’s Central Park in 1961 by Public Theater founder Joseph Papp. His “Shakespeare in the Park”, free for all the people of the city, aimed to demystify and democratize Shakespeare. Papp believed that access to world-class Shakespearean performance was a human right. These days, most states have a large annual Shakespeare festival performing a repertoire of classic plays outside every summer.

So what exactly makes these festivals so fun, and so central and long lasting in so many communities? Well, many regional Shakespeare Festivals are much more than simply an old play presented outside. Many companies offer workshops, pre-show events or concerts, lectures, children’s programing, food venders and more, creating a lively and celebratory experience, more akin to a county fair then a stuffy, bookish literary excursion. Shakespeare in the Park often feels like an “event”, a special outing. There is also the thrill of encountering these plays in the way they were intended to be seen: al fresco. Nature references abound in the plays: flora, fauna, weather imagery. Seeing the plays under an actual sky brings out their immediacy, their poignancy, and their authenticity.

It also adds to their “liveness”. In an outdoor theater, you never know when the real world might interrupt the theatrical world with a surprise interjection. Chief among the challenges of outdoor Shakespeare (and there are many) include critter visitors. Sometimes animals feel the need to add their own lines into Shakespeare’s plays. In my outdoor classical experiences, I have had mid-show encounters with bats, bees, squirrels, raccoons, lizards, deer, cows, and an adorable baby owl. There is also the unpredictable weather. I was once in a production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest in Vermont in which we had to cancel several performances due to a real life tempest. That, folks, is what we call irony. Some companies will have an indoor backup rain revenue, but oftentimes the show must go on come hell or high water. I was in a production of Romeo and Juliet in which a lightning storm split and passed us on both sides of the stage as we performed onwards; we were literally surrounded by the storm. Terrifying.

But these challenging factors are also what make classical festivals so thrilling. Outdoor Shakespeare exists between the joy and terror of the natural world. That prickly uncertainty of an evening outside perfectly mirrors the winding unpredictability of the plays themselves. The difficult natural factors (unpredictable weather, cold nights, rogue animals, uncontrolled spaces) can lead to moments of transcendent beauty and spontaneous theatrical magic: a line of verse flickers with renewed meaning, a supernatural moment echoes into an actual forest; fairies seems quite real; kings seem quite mad; armies seem endless; ghosts seem to emerge from the earth itself. As an actor and an audience member, I have repeatedly been flabbergasted by moments in outdoor theatres that could never have been predicted or rehearsed, yet fit Shakespeare’s creations so naturally that they feel serendipitous or almost divine, as if the natural world was cradling the plays and dusting them with a raw, powerful energy.

As our world gets more high tech, the rustic charm and traditional community-based joys of outdoor Shakespeare will become ever more vital and cherished. So I highly recommend that this summer you pack a picnic, rally the kids, and head to your nearest festival. At the intersection of the past and the present, these glorious institutions connect people to one another and to a long history of performance spanning continents, from Shakespeare’s Globe all the way to your local park.