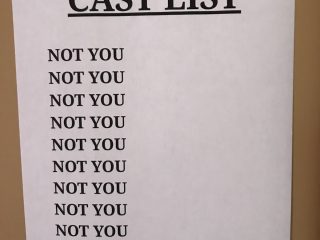

I’m sure we all remember it, heck, we might even be living it right now. Those halcyon days of educational theatre, where we spend months rehearsing a show, only to perform it two or three times over the course of a weekend in May. All that preparation, all that work, only to get a couple of cracks at glory.

That’s a reference to a typical high school schedule, where you must work around numerous conflicts and extra-curricular activities. By the time we’re in college, rehearsal schedules tend to clock in at 5 to 6 weeks, and performances tally anywhere from the high single digits to maybe 20 to 24. Hardly enough time to get bored, or the performances to become stale or uninspired. But what happens when we grab that brass ring at last, the long-running contract? It could be a tour, or a Broadway show, even some regional theatres that operate continuous schedules, producing the same show(s) for years on end? We’ve finally been rewarded for all our efforts, and that reward is…to do the same thing 6 nights a week for the next 6 months, even a year, maybe even longer?

A quick glance at my IBDB page might reveal I’m not an expert on this subject (I have a strict rule about the shows I do in New York City—they must be unpopular, even if they are very good).

But seriously folks, I do know a little bit about this. I’ve logged over 200 performances as Ravenal in Show Boat, heaven knows how many performances of the title roles in Jekyll & Hyde, and I just passed 100 as El Gallo in The Fantasticks. And I’m still going. And these minor feats aren’t even a blip on the radar to someone like Broadway star Howard McGillin, who totaled more than 10,000 performances as that creepy guy in the basement in The Phantom of the Opera.

Now, if that last paragraph of not-so humblebrag didn’t completely turn you off, stick around and let’s talk about how to keep your performances honest and true to the work, while the mileage keeps climbing.

As actors, we have certain responsibilities. We must stay true to the author’s and the director’s vision. We must keep our bodies and spirits in as good a condition as possible, so that we can access our own abilities. We are responsible to our fellow actors, to give them what they need to be successful as well. But how do we do this, when we’ve been doing the same thing, night after night, week after week, month after month? Ah, we have now arrived at one of my favorite theatrical bits of wisdom, one I couldn’t believe more strongly in if it were my own.

Okay it is my own. Don’t judge me.

As actors in a play, we are all kids in a sandbox on a playground. We can create whatever we want, build what we need, tear it down and start again. If I don’t like what’s happening in the center of the sandbox, I can go check out a corner for a while, and build something there. Maybe a friend will join me. Maybe everyone will come to this corner and we’ll all play together. Or maybe someone will drift to a different part of the sandbox and the whole process will start again. But there’s something none of us are ever allowed to do.

We can’t go play on the slide. Or the swings, or the merry-go-round. We all play in the same sandbox.

Do you follow me? We’re allowed to use different colors, as long as we’re all painting the same picture together. Some actors are comfortable giving the exact, same performance night after night. And that’s fine. Some actors are more comfortable listening and responding, and letting the performance flow more organically. Neither is wrong, both are viable, we just all should be striving for the same goal. Telling the same story, staying true to the direction and the text.

But what about the boredom? Doesn’t it get incredibly monotonous after a while? If the answer is yes, then maybe it’s time to move on to something else. I would argue that the show is never exactly the same from one night to the next. We are all humans, affected by the events of the day, and those events can (and probably should) have some impact on your performance. Sometimes you make the most amazing discoveries from the oddest of circumstance.

Not long ago in The Fantasticks, my fellow actors and I completely fell apart with laughter during one of the scenes (thankfully the scene is supposed to be funny). I can’t even remember what happened, I just know that we started to laugh and couldn’t get it back under control. The audience had a good time with us, and eventually we all got it together and proceeded with the show. The following scene is a simple, lovely monologue that I get to deliver, and I suppose it’s been fine enough. But this one day, after splitting our sides with laughter and tears rolling down our cheeks, I entered the speech practically exhausted. I was unable to do what I normally did, so I just said the words.

And the speech was never better than that one night, when I just got out of the way, and let the words do the work. The show has a handful of fans who see it quite often, and on this day our most loyal fan was there. We spoke after, and had to acknowledge the um…foolishness that happened on stage. But he offered up, the moments found after that were new, vibrant and alive, and I probably wouldn’t have found them otherwise.

So really, it’s not that hard to maintain a performance for a long period of time. Do your best to stay healthy, get along with all your fellow artists, listen and respond. Even if your performance is “by rote,” as long as you don’t shoehorn your work into the path of someone else’s, it can appear as fresh as opening night.

Now if you’ll excuse me, it’s almost half hour.