Finding monologues, at least for me, has always been a difficult challenge. Whether it be dramatic, classical, contemporary, or comedic, the struggle has always been real and honestly quite terrifying. I remember being in high school trying to make a moment, or even a fraction of a moment relatable in a monologue for auditions or during performances, but it never felt entirely fulfilling or realized– like I wasn’t doing enough. Then when I got to college, I was introduced to the ‘imaginary other’ and active monologues which changed my personal perception of the way I perform and how detrimental it really is to building your palate as an actor. I want to share with you the difference between active monologues and descriptive monologues, how they work in sync, and how you can find ways to improve your ability in both.

What is an active monologue?

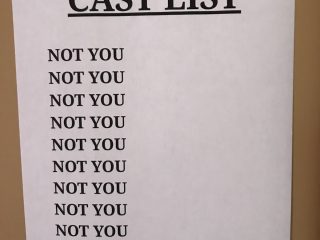

As performers of any sort, we see ourselves as storytellers. We have an ability that many people don’t have, so it is extremely typical that when we look for monologues, we look for ones that tell a story. For example, in auditions, we often see monologues that start with something along the lines of, “When I was 14 I lost my cat…”. This is the start of a descriptive monologue. Almost all descriptive monologues are brilliant. Very clear opening, we know what it’s going to be about. Awesome! However, when your teachers and other casting directors are looking at you for a role in the next play or musical, you’re more than likely going to be interacting with other people during the show and not monologuing about a moment from 3 years ago. So how do we play as a character in the moment? How do we show you interacting with something other than a memory? Let’s talk about it!

The one thing you should always remember when looking for an active monologue is ‘the imaginary other’. ‘The imaginary other’ is the person you’re talking to in the monologue when you’re performing. They’re not really there but the audience knows you’re talking to someone. It should feel real, purposeful, and connective in new and exciting ways. For example, if the start of your monologue is, “No, stop, you’re doing it wrong!” there are a million ways you can interpret that depending on who your imaginary other is. “No, stop, you’re doing it wrong” said to your brother or sister, will always be different than if you say it to your boss or classmate. You have a much more personal relationship with your sibling that is filled with years of love and frustration whereas with your boss or classmate, there’s going to be some hesitancy and more calmness. This is where incredible work can begin and where you can not only help tell a story, but also live in it as well.

How do you find active monologues?

It’s extremely difficult to come across an active monologue as a singular entity. Meaning that, because the monologue usually requires someone else in the scene, it’s hard to know what will actually translate in front of a director or teacher when nobody is there. I’ll be the first to tell you, I’ve looked on every website and monologue book to find the best that playwrights can offer. Sometimes you strike gold! Sometimes, you have to get a little scrappy. And here’s where the StageAgent monologue search function will prove to be your best friend! Take your time to search through the huge bank of monologues, finding out the context behind them and reading the show guide they’re from.

And of course, it goes without saying that you should read as many plays as possible. The best monologues I’ve found have never come from a random and sketchy site on the internet. They come from people who have assembled entire stories over the course of many years, perfecting each moment in a 2 hour show. When you read the play and you have a monologue, there’s nothing that can stop you. Simply because you know everything about the person you’re reading for and you can see just how much you relate to them as they interact with other characters in the story. If they get into an argument with another character in the show, consider using the other character’s dialogue as stuff your imaginary other would say to help build your monologue. For example, try reading this with a friend as an exercise:

You: “Oh my goodness, you scared me!”

Phil: “Oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to scare you!.”

You: “Don’t you ever do that again. I’ll have a heart attack!”

Now read it again, but this time make sure your friend doesn’t speak the line for Phil. Try to remember how they said, “Oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to scare you” the first time. Only perform using your two lines.

Continue to practice and BOOM. There you have it. You just created an imaginary other and a two sentence monologue!

You can always try the exercise again with another person in your life that you share a different relationship with. You’ll see an incredible change and see just how impactful creating different imaginary others can be!

How can we benefit from descriptive monologues?

While this is all incredibly useful, there will always be times when you’re not in control of what material you have to use for an audition or performance piece. Sometimes, the director or teacher will need you to perform something that is descriptive or straight up telling a story.

So how can we utilize this newly found tool of ‘the imaginary other’ in our work with descriptive monologues?

People don’t talk just for the sake of talking. There is always emotion. Feeling. A need to divulge information to someone else. That’s where we start. If we go back to the previous example of “When I was 14 I lost my cat”, the initial thought/question should always start with, “Am I talking just for the sake of talking?”. The answer will always be “no” and this is where your artistry and willingness to learn and expand your palate begins. If you know that the role you’re auditioning for calls for someone to be dry and cynical, maybe you decide that your imaginary other is a bully that you don’t want to give satisfaction to. Or maybe if the role you’re auditioning for calls for someone who is a hero, you can pretend your imaginary other is a small child that also just lost their cat and you’re trying to comfort them. Do you see what I’m saying? If you think about it, there are literally a million ways to transform a script without ever touching the actual dialogue. You can invoke happiness, love, anger, and disgust based solely on how you perceive your imaginary other. And don’t get me wrong, this process is not easy. I’ve struggled plenty trying to imagine my mother or best friends in the room with me arguing over something we would never argue about. But once you start practicing, your work will show the next time you grace the stage. Stay learning, stay perceptive, and stay kind!