If you spend enough time in the theatre, odds are you’ll eventually hear the name Bertolt Brecht. His work has inspired generations of theatre-makers and continues to make waves in the theatrical landscape today. But who exactly was he? Why the heck was he so revolutionary? Let’s take a look at Brecht’s life and what he believed about theatre.

A Brief Brecht Bio

Brecht was born in 1898 in Germany. At age sixteen, World War One broke out and Brecht registered for courses at Munich University to avoid being called to service. He studied drama among other things, and wrote his first full-length play, Ball, in 1918. After that, Brecht’s life was pretty much a series of moves around the world to flee persecution, while writing plays and developing his theories on how theatre should work. At one point, he wound up in Hollywood but was blacklisted as a Communist during the Red Scare. He returned to Europe, built his own theatre company, and died at age 58.

During his life, Brecht wrote about fifty plays, including Mother Courage and her Children, The Caucasian Chalk Circle, and The Good Person of Szechuan.

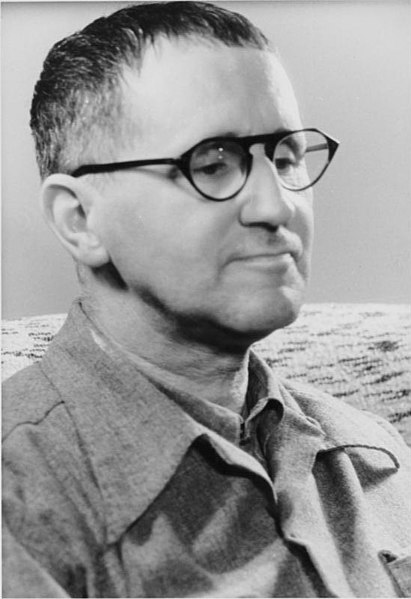

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-W0619-307 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

An Epic Life

So how did Brecht stand out from his fellow theatre-makers? Brecht developed what we call “epic theatre”. Throughout his career, he wrote a series of manifestos explaining what he thought theatre should accomplish and how to accomplish it. In a nutshell, Brecht felt that an audience should not become emotionally invested in a play or the characters. Instead, he wanted spectators to always be aware that they were watching a fictional performance. Why? Brecht felt that, rather than make us feel something, theatre should make us do something. To illustrate the concept, consider this: a group of theatregoers watches a play about poverty. They watch a scene in which a beggar is brutally assaulted. They feel terrible, perhaps they even cry. But then they are purged of those emotions and move on with their lives. Brecht wanted audiences to watch a play about poverty and not have that emotional release. He felt that preventing the audience from becoming emotionally involved would make people want to take action to change the problems illustrated in the play.

Brecht called this emotional distance “verfremdungseffekt”. In English, we usually translate it as “distancing effect”. Over time, Brecht figured out some tricks to achieve this distancing:

- The actors address the audience directly.

- There’s no attempt to conceal theatrical illusions. The backstage area might be fully visible, there are set or costume changes right on stage…anything to remind audiences that they’re watching a play.

- Actors often play multiple characters.

- At key moments, the action is interrupted with a song or an actor coming on stage with some sort of sign commenting on the action (in my previous example about a beggar getting assaulted, someone might come out with a sign saying “END POVERTY NOW”).

- There might be title cards projected on stage or placed on signs held by actors before each scene. The title cards act as a newspaper headline that explain what is about to happen in the scene (“Mother Courage loses her son”, for example).

Brecht’s hope was that audiences would be inspired to take action outside the theatre to change the world. In that sense, Brechtian theatre is quite politically charged. His work tackles issues of poverty, war, morality, and social justice.

Stanislavski vs Brecht

As an actor, performing Brecht usually means looking at your character in a different way than acting guru Stanislavski would advise (sorry, Konstantin). While Stanislavski wanted actors to look through the lens of their character’s internal psychological circumstances, Brecht encouraged actors to look through the lens of their character’s external economic circumstances. In other words, let’s say I’m playing a character named Bob who robs a bank. If I use Stanislavski’s methods, I might focus on Bob’s emotions and feelings to identify with him and figure out what would make him rob a bank. Maybe his wife is starving and that makes him angry, scared, and desperate. But if Bob is a Brecht character, I think about Bob’s economic status and the world around him to figure out why he’d rob a bank. His wife is starving and in Bob’s society, it’s dog-eat-dog, so it’s justified to rob a bank.

The (Rehearsal) Room Where It Happens

So how does all this work in rehearsal? One of Brecht’s key techniques involved having his actors assume a physical pose that conveyed the main story of the scene they were working on. He called this a “gestus”, and it was Brecht’s way of telling a story with simple stage pictures without involving emotional elements. Sometimes, he would even pull in strangers off the street and ask them what they thought was happening. When I assisted on a production of The Caucasian Chalk Circle, the director would ask me to close my eyes while the actors assumed their gestus. Then, I’d open my eyes and assign an aforementioned-headline to what I saw. The actors would then make adjustments as necessary to better clarify and communicate their intended story.

In addition, Brechtian directors will often have actors literally explain what their character is about to do and say in the scene before running the scene. One technique calls for an actor to say “I am [insert character name and social/political circumstances here], so I say [insert lines here]”. You might also be asked to come up with your own headline for your scene. These are all techniques designed to help the actors create a sense of emotional distance that will then translate in performance. If you want to see some Brechtian theatre in action, National Theatre has a great video introduction

An Epic Legacy

Brecht’s work and theories inspired generations of playwrights and directors. Tony Kushner, award-winning playwright of Angels in America, credits Brecht as a source of inspiration. In fact, Kushner crafted a translation of Mother Courage for The Public Theatre which starred Meryl Streep in the title role.

Brecht’s work can sound all very academic and head-y, and it kind of is! But don’t let that cloud how much fun Brecht can be. In fact, Brecht recognized the power of humor in making us think, even when it comes to talking about serious things, and often inserted moments of comedy into his plays. So if you’re looking for funny plays that might just inspire your audience to make the world better, bet on Brecht!